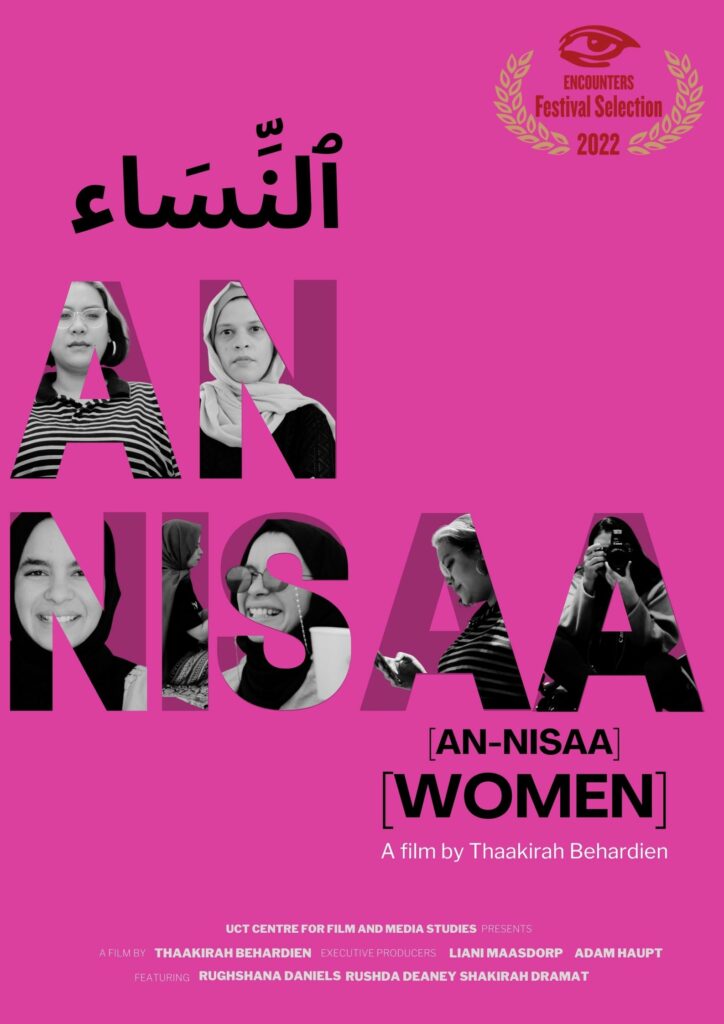

Thaakirah Behardien’s documentary “An-Nisaa” which won her the Best Emerging Filmmaker award revolves around three young Muslim women who use activism, social media, art and comedy to break stereotypes, writes Nabeelah Shaikh.

A Cape Town filmmaker is using her lens to change narratives and challenges the limited representations of Muslim women globally.

Thaakirah Behardien recently scooped the “Best Emerging Filmmaker” award at the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival. She produced a documentary named An-Nisaa, which translates to “women” in Arabic.

Behardien, 30, grew up in the community of Athlone in the Cape Flats. She had a passion for storytelling from a young age and this is what motivated her to pursue a career in filmmaking. She attended the University of Cape Town where she studied film. Behardien then completed an undergraduate degree in

film and media production. Thereafter, she completed her honours in film and television studies.

Behardien worked in the service industry for seven years where she gained valuable experience. “I specialised as a production coordinator working on projects for BBC, Netflix and Sony, among others. I then decided to go back to studying to pursue my master’s degree in documentary art,” said Behardien.

As part of her thesis she had to make a documentary, and that’s how she came up with the concept for An-Nisaa. Her documentary centres around the lives of three young Muslim female creatives and how they use activism, social media, art and comedy to break stereotypes and how they tackle taboo topics within their communities.

Behardien is often left frustrated by the stereotypical perceptions of Muslim women globally and she felt there was a need to challenge those representations. “The global image of the Muslim women is that we are always portrayed as oppressed and submissive. It always has some sad story or

element attached. And then you see how the narratives changed after 9/11. You suddenly see that Muslim characters are terrorists. They are represented only through their beards, niqaabs and the hijab. There isn’t a well-rounded 3D representation. I don’t think that it’s fair because it’s not the only narrative that exists. While there are restrictive regimes for every country and every religion, due to politics, I don’t know why as Muslims, we are only ever getting branded with the negative side,” said Behardien.

She told Al-Qalam that she always had a history of watching film and television and if one takes a look at what content is on screen at the moment, such as on Netflix or Hulu, Muslim characters always seem to be put in some kind of box. “Growing up, I noticed there weren’t enough accurate representations of Muslim women on screen. I looked at all the Disney princesses, thinking who do I look like? And you realise we don’t fit into any of those boxes,” said Behardien.

Behardien says she wanted to portray an accurate representation of what she feels as a Muslim woman in Cape Town. “As a young Muslim creative, myself, I am always keen to understand if other women felt a similar frustration with the global image of the Muslim woman. I think there is this movement towards more accurate representations of Muslims at the moment, for example, MO on Netflix, or Ramy on Hulu. But these are male characters and it’s from their perspective of representation. There is still a lack of Muslim women who are represented,” said Behardien.

She says the problem with the representations of Muslim women on screen is that they’re also treated as one homogenous body.

“We are not one homogenous body. We are a multi-pot of cultures, of race and diversity. That’s what An-Nisaa is. It was an opportunity for me to showcase particularly what I feel life is for Muslim female creatives in the Cape. And I specifically said in the documentary that it’s my lived experiences growing up in Cape Town, because I don’t want to diminish other Muslim women’s experience who may have experienced more oppressive or restrictive regimes, wherever they live,” said Behardien.

Childhood

She said she was only 11 when she decided she wanted to be a filmmaker. “I’ve always been a very visual person. As a kid, I was obsessed with film and television, and I was an avid reader. I had the kind of childhood where my parents would take me to theatres and encourage me in very artistic sense. A lot of people are often shocked to hear that my parents fuelled my motivation to be in the arts, because this is not what they expect from a conservative Muslim family. My mom was a teacher and she always encouraged that creative side of me.

I was always a storyteller, I think I tried to write my first novel at five-years-old,” said Behardien. She said she just felt naturally drawn to film because there’s just something about a moving image and what it can convey that she became obsessed with. “Growing up, there was a Muslim Cape Town based filmmaker, Zulfah Otto-Sallies – and she was a pioneer. She was way ahead in terms of representing Muslim stories on screen at a time when nobody else was doing it. And her father grew up across the street from my grandfather. I ended up studying her work in my academic research. I always had her at the back of my mind, thinking that it was possible to do it, that it was possible to be a filmmaker. If she was able to do it, I could too and that’s what I want to be for other young Muslim girls,” said Behardien.

Behardien said she wants to continue telling stories about representation. “Accurate representation on screen is something that I am passionate about, especially because I experienced growing up in a community where Muslim women were not represented. Growing up in the Cape Flats, the first thing you think about is gangsterism. And I think there is so much more richness and lively characters and stories coming from the Cape Flats and my community. I’m passionate about women-led narratives and telling female stories,” said Behardien.

Behardien said the support for An-Nisaa has been overwhelming. “The support for the documentary has been amazing. And for me, the reward is when I get messages from other Muslim women thanking me for representing them in this way. I believe this documentary is a love letter to the Muslim women of Cape Town and the Muslim women of South Africa,” said Behardien.

She added she would like to see more Muslim women taking up careers in creative arts. “I want to be able to inspire with my work but also to create conversations. It doesn’t always have to be positive conversations; the biggest enemy of any creative is indifference. It can be a positive conversation, tell me why you love it, but also tell me why you hate it. Just don’t be indifferent to it,” said Behardien.

Part of her prize from winning the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival award is having mentorship sessions with seasoned filmmakers in South Africa. “The opportunity and the exposure it brought to the documentary has been immense. The documentary has gotten great reviews and has been so well received by the Cape Town Muslim community. I honestly didn’t expect it. I didn’t expect it to be such an overwhelmingly positive response. It made me very excited,” said Behardien.