By Imraan Buccus

Adam Habib has been an influential figure in the South African public sphere, as well as at Wits. His recent piece, “Verwoerd’s political stepchildren: Managing fascists, Stalinists and the intolerant”, asks some important questions about our public sphere.

The toxic nature of our public sphere is more about how social media has changed the public sphere, something that we see around the world, than it is about Verwoed and our history of fascism. Around the world social media has allowed political entrepreneurs to rapidly build an online base which is then translated into space in the traditional media and from there to space in parliament, and sometimes then state power itself.

The early optimism about social media being a democratising force is now universally seen as misplaced. Newer studies, such as Richard Seymour’s brilliant book, The Twittering Machine, argue that social media rewards political extremism, manipulative and sadistic personalities and allows a few strident voices to appear as a majority. Also, by creating ‘echo chambers’ it divides society up into increasingly polarised views.

None of this is a uniquely South African phenomenon. As recent events in the United States have shown that country is now deeply divided into an increasingly extreme white right and an increasingly radical black and youth driven left. My own sympathies are firmly with the latter camp but as a scholar I must agree that the break down in the power of the traditional media has generated extraordinary political polarisation.

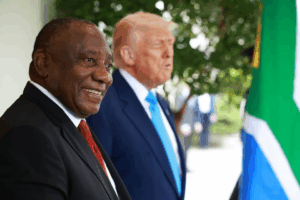

The dishonesty that has become common in our public sphere, including in journalism and the academy, is also not a uniquely South African phenomenon. Donald Trump is a notoriously dishonest individual but his followers still love his Twitter feed.

Social media has changed the public sphere as radially as Guttenberg’s invention of the printer did in 1440. We can’t go back to the old world in which newspaper editors decided who had access to the public sphere and on what terms. These days someone like Donald Trump or Julius Malema has more power in the public sphere than most newspaper editors.

Social media driven forms of right-wing extremism, usually in the form of authoritarian nationalism, are often a genuine threat to democracy. Habib is absolutely correct to argue that democrats need to think very seriously about how to engage in this new reality. Habib’s argument, of course, is that most decent people relate to social media via a version of George Bernard Shaw’s famous maxim “Never… wrestle with a pig, you get dirty; and besides, the pig likes it.” In more contemporary language the maxim would be: Don’t feed the trolls. This makes perfect sense in terms of protecting one’s sanity, but Habib is right to argue that it doesn’t make sense in terms of protecting democratic norms in society.

When a figure like Trump or Malema is not challenged and can build a huge online following that can be translated into media coverage and then political power democracy is at real risk. Malema is a highly authoritarian personality whose contempt for democratic norms is obvious. He and his party are also deeply compromised by their association with the tobacco mafia, the looting of VBS bank and their support for the Zuma faction of the ANC. The EFF is an authoritarian political project, that many commentators have described as containing fascist elements, that aims to mobilise the poor in order for its leadership to force their way into power and become Zuma style predators on the public purse.

Habib is entirely correct to argue that treating Malema and the EFF as if they are credible democratic actors is a form of appeasement, a form of appeasement that could have catastrophic consequences for society down the road. Habib is also correct to note that Cyril Ramaphosa’s strategy of appeasement is both cowardly and extremely dangerous.

Of course, the EFF is not the only faction in our society that is fundamentally dishonest, brazenly in support of elite predation and working to build support via social media. The Zuma faction of the ANC, which is now aligned to the EFF, operates on a very similar basis. Black First Land First, which is now is conflict with the EFF but it continues to support the Zuma faction of the ANC, also operates in a similar way. This project has gone further down the rabbit hole of dishonesty than any other political grouping and has embraced all kinds of wacky conspiracy theories.

Yet much of the old-fashioned media allows its agenda to be set by what’s happening on social media. People with a big voice on social media are often given significant space in the old-fashioned media. Well documented histories of thuggery, dishonesty and corruption are no barrier to being received as a credible actor in the media. The same is often true in the academy. Black First land First’s attraction to wacky conspiracy theories, ranging from the usual 5G stuff to the claim that the EFF is really a front for a British aristocrat to lauding a purveyor of alien reptile conspiracy theory as a great figure, is all over his Bell Pottinger built website. Yet his name regularly appears in academic papers and books as if he is a serious intellectual.

Societies across the world are struggling with how to secure democratic norms in this new world crated by social media. No one has all the answers. Part of the solution probably lies in the need for a body like the United Nations to take ownership of the big social media firms and run them on a public interest basis that explicitly prohibits the deliberate circulation of dishonesty. Conversations about these kinds of macro-level strategies are important.

But we also have to decide how we engage the public sphere as it currently exists. Habib’s wager is that we should not allow the trolls to take over the space and that we should contest their thuggery and dishonesty at every point. It’s an open question as to whether or not the majority of us have the time and energy to be continually dealing with Twitter mobs. But it is certainly true that in formal politics, the media, the academy and civil society a clear line should be drawn between people who try to be honest and people who engage in brazen dishonesty; between people who try to do the right thing and people who engage in brazen corruption; and between people who engage in debates in a democratic manner and people who use online thuggery and intimidation to close down space and intimidate others.

If we can’t draw these lines we will only have ourselves to blame if the poisonous bile that floods social media eventually damages our democracy beyond repair. Sunday Times

Buccus is research fellow in the School of Social Sciences at UKZN and academic director of a university study abroad program.