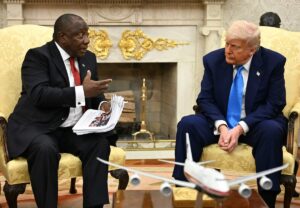

Photo source - PickVisa

By Ebrahim Rasool

In the previous column, we attempted to illustrate how the Prophet (s) carefully constructed the City-State of Medina, and through his negotiations with the various constituencies, left us with the Charter of Medina, his own governance of this polity, as well as his final sermon on Arafat, and through these, left us with a legacy that constituted statecraft for a more inclusive, rights-oriented, and free society.

The critical question – if we are to look towards a contemporary application – is whether this Medina model is in any way equivalent with today’s models of participative democracies?

The argument would be that the immediate successors to the Prophet (s) would have imbibed the underlying values of what he had practiced in Medina and sought to be faithful in their understanding and practice thereof. The formative period of Muslim statecraft would, therefore, consist of firstly, what Muslims escaped from in Mecca; secondly, by what the Prophet (s) had constructed in Medina; and thirdly, by the practice of the four Caliphs as they succeeded him.

For us to salvage these ‘first principles’ of Strategy and Statecraft we would necessarily have to mine these periods, but also understand why these periods appear to have receded and faded in the Muslim imagination, and why the aberration has persisted and rendered itself normal.

An ‘aberration’ and departure from the first principles of Islam, as articulated and practiced by the Prophet and his Companions, occurred after the establishment of the Umayyad Dynasty which was hereditary, without popular inclusion, and displayed the hallmarks of authoritarianism, and left the Ummah with three basic propositions that justified the exclusion of the popular will when it came to succession and the establishment of representative governance:

The first one was described as ahl al-hal wal-aqd – those qualified to elect or nominate for the citizenry – which usurps the right of the citizens to participate by giving it to a group, who decides, pledges allegiance – bay’ah – and through that, the entire community or nation is bound to the choices of that group, without the right to participate or object. The second method – or aberration – is described as wilaya tul ‘ahd or the practice whereby the incumbent invests a successor with authority of leadership, and this is often used with hereditary succession. The third method – which is worse than an aberration – is the practice of shawkah or the use of force, usually through military intervention, to replace one leader with another.

These aberrations set the template of monarchical and dynastic rule and authoritarian governance for centuries. Yet, for all three of these aberrations there was no textual justification, either in the Quran or Prophetic Tradition, which could be used to exclude the popular will in the election of leadership. Thus, it is incumbent on current generations to rescue the first principles of Islam from the aberrations. Luckily, however, new hybrid models of governance had emerged in Turkey, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Africa, which offered a range of options for Muslim-majority societies emerging from conflict to choose from. Options based upon a return to first principles and ‘wasatiyyah’ – middle, balanced way and based upon the convergence of the values inherent in the Maqasid-al-Shariah.

Political legitimacy is rooted in the concept of Shura or consultation. The Quranic injunction to the Prophet (s) is: “And consult them in the affairs of life.” The Ummah is described as a community who “conduct their affairs through mutual consultation…” The litmus test is that it is primarily consultation about mu-amalat matters of society, not worship; and that it must result in justice for the public good and the public welfare. If we assume that linguistically – Shura means mutual consultation – and textually – both the Quran and the Prophetic Tradition require popular inclusion for leadership legitimacy, then scholarship also agrees that the principle is inviolable and the form variable enough to embrace democracy, but through a variety of means.

Aberration

Many of the supporters of authoritarianism (as described in the aberrations) seek legitimacy from the way in which the successors to the Prophet – the rightly-guided Caliphs ascended to leadership. An examination of these would indeed show pragmatism in form, yet adherence to the principle of the popular will from simple approval to actual election.

This is clarified in part by Al-Māwardī (in al- Ahkam al Sultāniyyah, p.21)when he explains that there can be an intervention by the predecessor to influence succession, but not without popular approval: “There is consensus of opinion regarding the permissibility of concluding the contract of imamate (leadership ) based on the covenant made by the former imam due to two reasons to which Muslims had acted accordingly and which are reported not to have been denied by any of them: the first reason is that Abu Bakrnominated Omar to succeed him after death. Thereafter, Muslims confirmed the imamate of Omar based on the covenant made by Abu Bakr. The second reason is that Omar referred the matter of caliphate to a consultative council and the entire members of the Muslim community approved that decision.”

Filling in an important gap, Mohammad Salim Al-Awa (Fi al-Nizām al-Siyāsi li al Dawlah – On the Political System of Islam p.71) gives context to Abu Bakr’ssuccession of the Prophet: “The first pledge of allegiance made at the courtyard of the clan of Sa‘idahaimed at nominating Abu Bakrto handle the affairs of the Islamic State by people of insight. The public pledge of allegiance concluded the next day was like a referendum on such nomination so as to give the Muslims the chance to express their opinions regarding choosing the president of the state.” In this succession by Abu Bakr, while Ali felt that he may have had both a popular majority and a military superiority, he chose not to test either so that the Muslims did not – at that moment of birth of popular will in early Islamic history – undermine the consensus with popular approval and set an unfortunate precedent for either challenging the popular will or invoking force.

The succession by Uthman was another evolution which started with a shortlist of candidates presented to a council of seniors or in today’s terms, an electoral college – but again presented to the citizens and supported by popular approval. Ali’s succession was more of an election by popular acclaim, as Muslims gathered at the mosque in support of Ali’s accession as leader.

Each of these methods of succession had its unique features as well as its unique reasons: Umar’s pledge to Abu Bakr on confirmation of the Prophet’s (s) demise was to prevent a vacuum that could destabilise Medina; while Abu Bakr on his deathbed understood how crucial Umar was to the expansion and consolidation of Islam, therefore, nominating him; and on Umar’s assassination, with a few candidates available, a council was established to evaluate each one’s fitness for the post, with Uthman emerging as the choice; and finally, on Uthman’s death, popular acclaim installed Ali as his successor. Yet, in each the CANDIDATE was presented for popular approval before being installed. Our challenge today is about implementing the principle of popular approval given the vastness of the populations and the logistics involved in getting an accurate count. This presents a methodological challenge, not a challenge of principle!