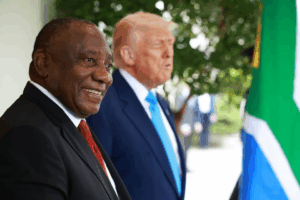

[Photo Credit - The Atlantic]

The Maqasid al Shariah as the Fountainhead of Political Practice

By Ebrahim Rasool

Following how scholars like Yusuf al Qaradawi and Hassan al Turabi conceptualized Islamic thinking in response to the Arab Spring and the need to rethink Muslim societies in its aftermath, my response was to synthesise such thinking with my South African experience, and through the application of the Maqasid al Sharia – the intents and values of the law.

The beauty of an approach to Islam that is based on the intents (Maqasid) of Islam is that it draws on the purest human instinct or Fitrah, a disposition inclined to good and towards attaining the objectives set by God, when armed with divine guidance.

The scholar, al Juwayni, in his book Al Ghayyaath, therefore declared hypothetically, that should there be an occasion where Muslims would lose the heritage of laws, rulings and practices inherited from the jurists, it would be possible to salvage such from the principles and objectives from which the law emanated in the first place. The socio-political and economic challenges – the public good – facing Muslims today require Muslims to return to the intents of Islam, especially in pursuit of Peace, Justice and Inclusion, and the incorporation of these values into processes of peace-making, transitional management and imagining new forms of statecraft.

The public good must be at the heart of statecraft. Al Juwayni saw the notion of public interest as interchangeable with Maqasidus Sharia, while Abu Hamid al Ghazali and Fakhrudin al Razi saw the notion of an unrestricted interest as fulfilling the same purpose. Najmudin al Tufi goes so far as to say that the exercise of public interest (Maslahah) should be given precedence if it is in accordance with theQuran and the prophetic tradition. Al Qarafi is bold enough to declare that a Maqsid (objective) of any act in Islam would not be valid if it does not fulfil the public good and if it does not avoid mischief.

The classical scholars of Islam identified three levels of the Maqasidus Sharia or objectives of the law. The first level is that of necessity or Dharurat: the necessity to preserve life, faith, soul, mind, wealth, offspring, and honour. The second level is that of need or Hajiyat: ensuring that which is essential for human life, like sustenance and shelter. And the third level are that which beautify life – the adornments or Tahsiniyat. It is around these sets of intents that Islamic statecraft must be conceptualized.

Later scholars, using the classical basis outlined above, was able to upgrade the thinking of Muslim thought by infusing the classical intents of Islam with contemporary experience and need. Tahir ibn al Ashur, for example, ranked objectives relating to the collective as higher in precedence than objectives relating to individuals. Rashid Rida included objectives relating to political reform and women’s rights in his understanding of Maqasidus Sharia.

Muhammad al Ghazali included justice and freedom amongst the intents. Yusuf al Qaradawi saw the necessity of including human rights and dignity. Both Rachid Ghannoushi and Muhammad Khatami included democracy among the objectives because the former saw it as critical to justice, while the latter understood it to be the antithesis to dictatorship, which is anti-Islamic. This collective work has today blessed us with a set of intents and objectives consistent with the challenges that Muslims would face in the world today.

It becomes possible to set out the primary intents of Dharurat (necessities) from which to derive contemporary applications, drawn from the classics, but made current as follows:

– From the classical Intent of the Preservation of Offspring, Tahir ibn al Ashur posits the contemporary Preservation of the Family.

– From the classical Preservation of Mind, is derived the contemporary objective of the Pursuit of Knowledge and Access to Information.

-From the classical Maqsid (Intent) of Protection of Honour, the work of, amongst others, Yusuf al Qaradawi takes us to the contemporary need for Human Dignity and Human Rights.

– From the classical Preservation of the Soul, Rida and Afghani posited that Fitrah or Natural Disposition of the human soul requires Hurriyyat or Freedom and Choice.

– From the classical objective of the Protection of Religion, al Ashur argues that the contemporary application is for the Freedom of Belief based on the principle of “no compulsion in religion” (la ikraha fi deen) rather than the political exigency of “punishment for apostacy” (had al riddah); and

– From the classical Preservation of Wealth, should be the contemporary objective of Human Development where wealth resorts today in the acquisition of education and skills, the access to services and employment, and the need for more equitable distribution of wealth.

From these Maqasid can be derived the further objectives and intents that fulfill the Hajiyat (needs) and the Tahsiniyat (adornments) that make life fulfilling for Muslims and all human beings, as God intended.

Such an approach reconnects Muslims to the overall foundations of Islam: If the name of our religion (Islam) is derived from the root word for peace, then peace must be germane to our existence and statecraft. Similarly, if the first attribute of God is “Most Merciful” and the mission of the Prophet (s) is to be “a mercy unto all creation”, then harshness cannot be that which Muslims are known and feared for.

And if the Qur’anic depiction of the global Muslim community is “Ummatan Wasatan”, or a community that is “most middlemost”, in other words, one that is balanced, in the centre, and avoiding extremes, then this becomes another core ingredient of our societal practice. Our intents and the foundations of Islam will need to the yardstick by which we measure our relations with contemporary political, social, and economic practices so that we neither are simple rejectionists or uncritical adopters of that which is new and different.

The antidote to both instincts is the presumption of continuity where Islam encounters difference and variety. The presumption of permissibility of a matter until it is proven to be forbidden, was critically important to the evolution of Islamic thought and practice. These would be important counterbalances to the Muslim today who is initially suspicious of political or other systems until permissibility is proven. Islam’s basic assumption is that people will act in pursuit of good and practices should, therefore, be regarded as basically permitted, unless proven otherwise, and their culture and custom should be regarded as acceptable, unless proven to contradict the divine script.

The Intents of Islam provide the critical and principled ingredients for dealing with injustices, for peace-making, transitional management and statecraft, and the imperatives of balance and the presumption of continuity allow Muslims to find new and different ways of solving persistent problems founded on enduring intents and possible new approaches.