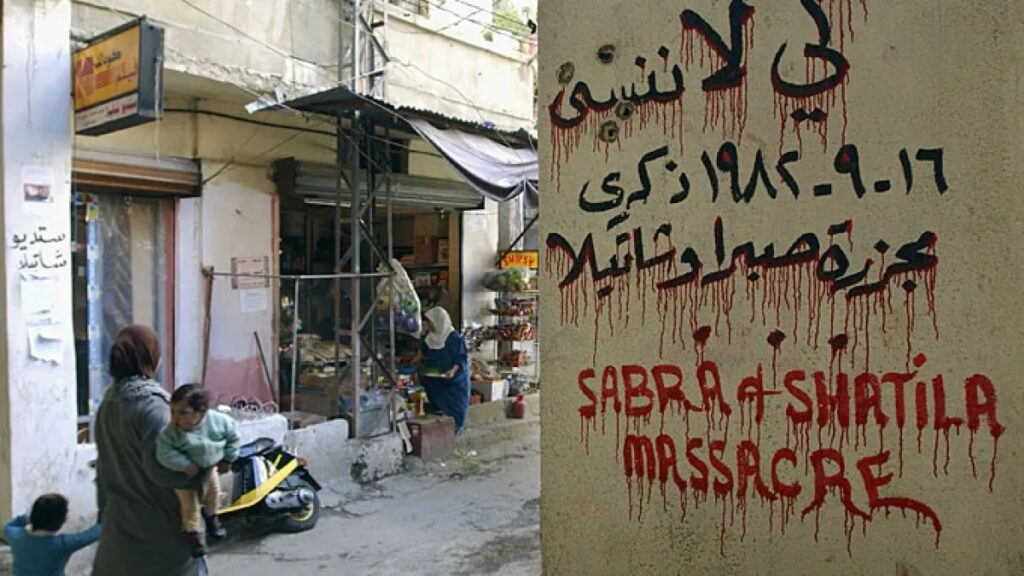

[Photo source - Al Jazeera]

Remembering Lebanon’s Sabra and Shatila massacre in an African context compels us to confront our own histories of violence and discrimination, writes Ali Komape.

As we commemorate the 31st anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, it’s crucial we view this tragic event through an African lens.

Although it unfolded in the Middle East, the lessons and implications of this dark chapter in history resonate deeply with the African continent, emphasising the global responsibility we share in preventing such atrocities.

The massacre, orchestrated by Lebanese Christian militias, aided and abetted by the Israeli occupation forces, claimed the lives of more than 3 000 Palestinian refugees, including women, children, and the elderly, between September 16 and 18, 1982.

The brutality of the massacre and the suffering endured by Palestinian victims remains etched in our collective memory as a stark symbol of the consequences of unchecked hatred, racism, discrimination, and violence.

Leading to this catastrophic event is evidence of Israel’s involvement in the killing and maiming of unarmed Palestinians.

In 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon with the stated goal of removing the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) from Lebanon. This invasion eventually led to the siege of Beirut, where Sabra and Shatila refugee camps were located.

After besieging Beirut, Israel controlled access to the city, including the Sabra and Shatila camps, and allowed Lebanese Christian militias, specifically the Phalange, to enter the area. Israel maintained close ties with Lebanese Christian militias, including the Phalange, and provided them with military support and assistance during the invasion.

The Phalange had a history of hostility towards Palestinian refugees and was motivated by a desire for “revenge” following the assassination of their leader, Bashir Gemayel, who they falsely believed was assassinated with the help of Palestinians.

Despite knowing of the animosity of the Phalange towards Palestinians and fears that they would seek retribution, the Israeli military allowed the Phalange to enter the Sabra and Shatila camps. They surrounded the camps and provided them with logistical support during the operation. During the massacre, which lasted several days, Israeli troops were positioned nearby but did not intervene to prevent or halt the killings.

This inaction has been widely criticised as a failure to fulfill a moral and legal obligation to protect occupied civilians under international law.

Africa has its own painful history marked by colonial occupation, genocide, ethnic conflicts, and civil wars. From Rwanda to Sudan, Angola to Sierra Leone, Namibia to Zimbabwe, the continent has borne witness to the devastating consequences of racism, division, and colonial violence.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre, although geographically distant, serves as a poignant reminder that we are all interconnected in our pursuit of peace, justice, and human rights.

One lesson we can draw from this tragic event is the importance of international intervention to prevent and address conflicts.

In Africa, we have seen how delayed or inadequate international responses have allowed violence to escalate and innocent lives to be lost.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre should remind us of the critical need for swift and decisive action when such crises occur, regardless of where they happen in the world.

Furthermore, the massacre underscores the significance of fostering tolerance and understanding among diverse communities in former colonial territories.

Africa’s rich tapestry of cultures, ethnicities and religions offers both an opportunity and a challenge. It is incumbent upon us to learn from the mistakes of the past and work towards building inclusive societies where differences are celebrated rather than exploited.

Despite the UN General Assembly passing a resolution declaring the Sabra and Shatila massacre an “act of genocide” and the Kahan Commission, an Israeli inquiry into the events at Sabra and Shatila, finding that Israeli officials bore responsibility for the massacre and concluding that former defence minister Ariel Sharon, in particular, bore personal responsibility for failing to anticipate the consequences of allowing the Phalange into the camps, no one has been brought to justice or held accountable.

This failure to bring those responsible to justice for the crimes in Sabra and Shatila teaches us that without justice, acts of crimes can and will be repeated by the perpetrators.

Remembering the Sabra and Shatila massacre in an African context also compels us to confront our own histories of violence and discrimination.

We must acknowledge the scars of colonialism, apartheid and internal conflicts that have left lasting wounds. By acknowledging our own painful past and promoting reconciliation, we can contribute to a more peaceful and just world.

As we reflect on the Sabra and Shatila massacre as Africans, we must recognise that our responsibility to prevent such horrors extends far beyond our borders. It is a global responsibility rooted in our shared commitment to humanity, justice, and peace. Only by learning from history can we hope to build a more equitable and harmonious future for all.

*ALI Komape is the campaigns and communications manager at #Africa4Palestine.