By Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool

In the Spring 2025 edition of the journal Jacobin, a piercing question is asked: What creates an aversion to progress? Three possible reasons are averred: firstly, it could be the idea that a community’s best years are behind them, that somehow their golden age has passed, and whatever could be thought of has been thought, and there is no need for new thought; secondly, it could be that progress is frightening, that it could disturb or disrupt every neat and comfortable assumption of that community, and that anything new could be a contaminant to a pre-existing morality and intellect; and thirdly, the need for progress is acknowledged but the wherewithal, the skills and resources for progress in an unmoored world is not available to that community or its scholarly sector.

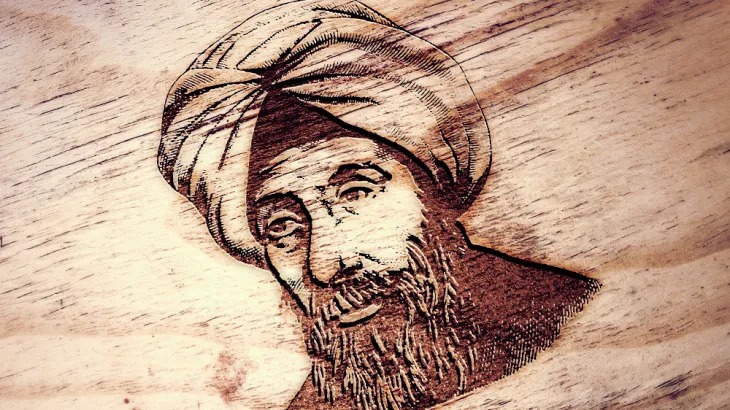

In preparing for my keynote address to an illustrious audience gathered by the Muslim Thinker Forum in Cape Town recently, this interrogation shaped my evaluation of the state of the contemporary Muslim ummah, an ummah who today, many centuries later, are mere strangers to, and consumers of, their own gifts to the world, whether the inheritance of Al Khawarizmi’s algorithms that fires the digital revolution or Al Battani’s pioneering work in astronomy and trigonometry.

My conclusion is that the ummah contains elements of all three of the proffered reasons for the absence of progress: we possess an inordinate nostalgia for a great past, so much so that we did not trust future generations with the motor for regeneration – ijtihād or the independent critical reasoning – and promptly shut it down; we certainly are suspicious of anything new or innovative, hence the free and abundant usage of what has become a condemnable pejorative word, bid’a or innovation; and thirdly, even if we could overcome these two, the wherewithal for progress through critical thought and reasoning is lacking when even those most educated in the non-worship professions abdicate from thought, genuflect to those proficient in worship, and affirm the historical barriers to their participation in the jurisprudence of the socio-political-economic-cultural-and professional disciplines. This is intellectual abdication.

A few in my generation, growing up in the heart of the apartheid experience in the 1970’s and the 1980’s, through the transition of the 1990’s, were also largely up against the theologians of worship. They too told us to avoid the socio-political, preferring that we stand up only for fajr, not for justice. They too confronted us for our lack of expertise in Arabic and Islamic knowledge as the key barriers to our engagement in the required ijtihād in the face of rampant racism, repression, and dispossession inherent in the apartheid injustice. They then already advised that we stay in our lane. They ignored the fact that our generation learnt the Qur’an and Sunnah in community halaqat (study circles), in the confrontation with injustice, in solitary confinement in apartheid jails, and in the deep underground, hounded by the security police. We often had to determine what Allah asked us from the cardinal maqasid or divine intents that were so clear in their absence and denial.

It was in real life that they had to find wasatiyyah (the middle ground) in the heat of both battling injustice and our own anger. It was often in the absence of our own leaders that we had to find common causes with people of other faiths and ideologies and learnt the lessons of building the hilf al-fudul (the coalitions for virtue). It was in the heart of constitutional negotiations that we had to find the formula for a society of mutual co-existence and cooperation, expressed as a Darus Shahada, as a move away from the hostile abode. It was in the nascent governance structures, where our professionals were largely absent, that we had to find formulas for services amidst a racially skewed edifice. Because we strayed from our lane, we influenced the construction of an Islamophobia-free country.

It was precisely the ijtihad of that generation of intellectuals and activists that created the space for today’s Muslims to thrive in their professions. They have the freedom even to abdicate from the responsibility of their knowledge and defer to clerical knowledge. Even my generation deferred to clerical knowledge for worship but knew that should we wait for their Arabic and Usul to pronounce on apartheid, the imperatives of fiqhul muʿāmalāt (the jurisprudence of the world) would have passed us by at the moment of its greatest need.

It is today the absence of ijtihad in the fiqhul muʿāmalāt that makes of Muslims the perpetual victims of history. The state of the ummah is defined by an enormous lag in both the number of patent registrations and scientific-technological publications our intellectuals and professionals bring to the contemporary world. The antiquated state of our muʿāmalāt is evident in the ambiguity we have about democracy, human rights and freedom, and its impact on our systems of governance, mobility of women, and even in the absence of a strategy and vision for Palestine, beyond ending the genocide.

In the face of these, we possess great moral righteousness, but not always moral clarity, the clarity that is of the Prophetic quality in which there is a clear analysis of our contemporary reality (the jāhiliyyah – era of ignorance – in the Prophet’s (PBUH) time is the barbarism we confront today); opposed by a compelling tawhidi vision of an integrated, inclusive and equal world; and attained through a strategy of jihad (multi-faceted struggle), founded on ijtihad, without which jihad is reduced to its component of qitāl– warfare. The Arab Spring represented a moment in which a great opportunity – the overthrow of tyranny – was sacrificed because our instinct was nostalgic: how do we recreate both the essence and form of the Prophetic era, and in this, we gave room to those who feared the Arab Spring to conspire for counter-revolution.

Professor JK Galbraith once said: “The more uncertain people are, the more dogmatic they become”. Dogmatism isn’t intellectualism! If anything, it is at best non-intellectual because thinking has been removed, and nostalgia and imitation have become our currency. This is sustainable in the fiqhul ibadāt (worship) because the Prophet (PBUH) said: “Pray as you have seen me pray”. But their limitations are evident in the muʿāmalāt, where certainly the essence must be transposed, but the form transformed. Dogmatism, at worst, is anti-intellectual. It actively opposed thinking: it creates a blanket ban on innovation by invoking bid’a; what it doesn’t understand or tolerate, it labels with takfirism (excommunication); and in its apparent quest for purity, it avoids contamination from other faiths, ideologies, or genders. This potentially creates an existential crisis for the ummah, whether by relevance or by Allah’s sunnah to replace a people who fail in their purpose.

I sometimes joke that the strength of the Ummah is that it has no pope, and the weakness is that is has no pope. The strength lies in the fact that we have never had a clerical class to whom we outsourced our thinking, no fragmentation of scholarship into theological and secular, and no restrictions on who can and cannot think, thus creating a festival of ideas, creativity and progress. The weakness is that in times of fragmentation and barbarism, we have no sense-making and consensus-forming centre, and in a place like South Africa, we have a mufti (an edict-giver) in every suburb, whose first edict is often to takfir his Muslim rivals.

It is under circumstances in which the Ummah finds itself a victim of the surveillance state, occupation, and Islamophobia that we most need leadership based on ijtihād and jihad. In the quest for such leadership, we are reminded that the founding revelation in the Quran was the invocation to read, use the pen, and uncover unknown knowledge. In the quest for leadership, the Prophet (PBUH) recommends that when two or more are set for an endeavour, the first thing is to elect a leader. Clearly, no leadership vacuum must ever be allowed! But the Prophet (PBUH) also admonishes that those who desire leadership must be denied leadership. Leadership is neither a claim nor a title; it is earned through service to humanity and acclaim by your community.