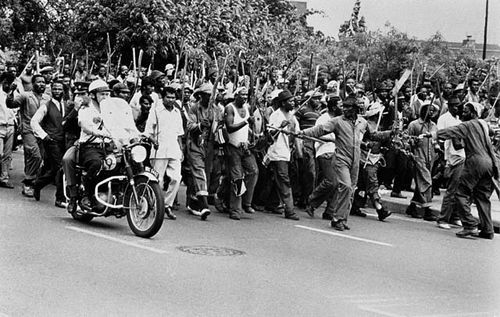

Municipal workers marching through the city centre escorted by a municipal traffic policeman [SA History]

By Imraan Buccus

On 9 January 1973, workers at the Coronation Brick and Tile factory in Durban went on strike. They had no union, and the strike was self-organised. Tomorrow marks 50 years. Following this, more strikes followed and on 25 January workers at the huge Frame textile factory came out.

After the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 the liberation movements had been banned, and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu) driven underground. For more than a decade open resistance to apartheid within the borders of South Africa was largely suppressed.

The Durban strikes changed that. The strikes led to the creation of unions in many industries, and then the formation of the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu) in 1979. Fosatu retained its independence from the elite controlled politics of the African National Congress. In 1985 it was replaced with the ANC aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu).

Today many young people assume that it was the armed struggle that defeated apartheid. This is not true. The defeat of the apartheid army by the Cubans at Cuito Cuanavale in Angola in 1988 was certainly a factor, as was the international movement against apartheid. But it was, above all else, the mass democratic struggles taken forward by ordinary people under the banner of Cosatu and then the United Democratic Front (UDF) that made apartheid non-viable.

The Durban strikes will not be widely celebrated as a key moment in our liberation, partial and compromised as it is, because they happened outside of the control of ANC. Indeed, the ANC was taken by complete surprise when the strikes happened.

The national history that we are given is very often a history of the ANC, a history that marginalises people, organisations and events outside of the ANC. And of course, as the subaltern studies academic movement in India showed, official history under former national liberation movements is inevitably a history of national elites. There is a scant chance that we will see a glossy Netflix film on the strikes. Working class people and their political actions are very seldom given their due.

The Durban strikes did not only happen outside of the control of the ANC. They did not only introduce ordinary working-class people as key political actors. They also began the development of a democratic form of politics that was in direct contrast to the authoritarianism of the ANC in exile.

This set up a fundamental political split within the national liberation movement. The political importance of that split became all too clear during the disaster of the Jacob Zuma presidency.

Today unions are on the backfoot. The Cosatu unions largely represent public sector workers and have been deeply compromised by their relationship with the ANC. Many of the industrial unions are in crisis due to the massive and ongoing deindustrialisation of the country. Numsa, the only union that has been able to effectively expand into new areas of work, is excellent at servicing its members but has not, as it hoped, been able to give overall leadership to the working class. Its political party, launched right before an election and then having to navigate the Covid lockdowns before it has built solid structures, failed.

Some analysts think that the exclusion of Cosatu from the new NEC of the ANC, could, along with the exclusion of the SACP, push Cosatu to take a more independent line. It is not impossible that these hopes could be realised but we should remember that the expulsion of Numsa from Cosatu in 2014 due to the union’s hostility to Zuma did not, as many had happened, lead to a strong working-class challenge to the ANC.

Unions remove important actors in society and, because they have dues paying members, do not, unlike the NGOs, depend on donor funding. This gives them significant autonomy in class terms as well as stability.

But with mass unemployment being a structural feature of society, and with youth unemployment being through the roof, unions will not be able to represent the majority. An effective class politics has to organise the unemployed and the informal workers at real scale. In Durban there has been significant advances in this regard in terms of organising shack dwellers, many of whom work as domestic workers, ad hoc construction workers and the like. But none of the existing trade unions have been able to grasp the nettle of the future and organise the unemployed or informally employed. This work of mass organisation is still to be done.

The unions and then federations that came out of the Durban strikes developed as an alliance between workers and university students and academics. Richard Turner, the philosopher and political science lecturer who was assassinated in 1978 was an important figure. But others, such as Omar Badsha, Hilton Cheadle, Gerhard Mare and Eddie Webster were also important players. David Hemson was probably the most influential of the academics and students who went into the unions. After being forced into exile he joined the ANC and was then expelled from the party in 1979 while lecturing in Tanzania. His ‘crime’ was to insist, much as Fosatu would do, that workers should not trust the elite nationalism of the ANC and should insist on the intended power of the organised working class.

Unlike in the 1970s and 1980s very few of our academics and students have gone into building mass democratic organisations during the post-apartheid period. Intellectuals have tended to go into NGOs or, less often, into tiny and often toxic sectarian groups.

History has proved Fosatu and the likes of Hemson correct. The ANC did, as they feared, betray the working class. And unlike the generations of intellectuals in the 1970s and 1980s very, very few of our intellectuals have committed themselves to the work of supporting the organisation of the unorganised.

Today as the hopes that were birthed with the 1973 strikes lie in tatters there is much to learn from the workers and intellectuals who, together, built the mass democratic movements that did more than any other force to defeat apartheid.

***Dr Buccus is editor of Al-Qalam