Ali Shariati and the Fanonian Interlude

By Ayesha Omar

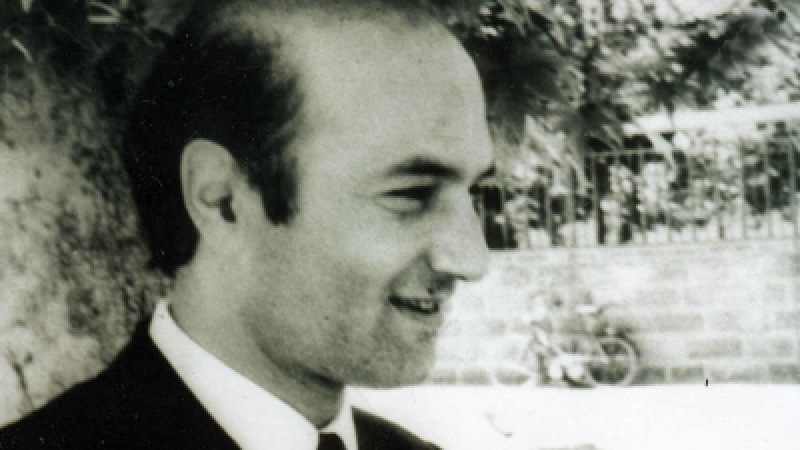

Ali Shariati (1933-1977) stands as one of the most influential and controversial intellectual figures in 20th-century Iran. A sociologist, historian, and Islamic reformer, Shariati’s revolutionary ideas played a crucial role in shaping the ideological landscape that preceded the 1979 Iranian Revolution. His unique synthesis of Islamic theology, Western social theory, and anti-colonial thought created a potent framework for social and political change that continues to resonate in Iran and beyond.

Born in Mazinan, a small village in Khorasan, Shariati’s intellectual journey was shaped by his exposure to both traditional Islamic education and Western philosophical thought. His father, Muhammad-Taqi Shariati, was a reform-minded Islamic scholar who introduced young Ali to both classical Islamic texts and contemporary social issues. This dual heritage would become a defining feature of Shariati’s intellectual project as he sought to reconcile particular Islamic traditions with modern social and political realities.

Shariati’s encounter with the work of Frantz Fanon during his studies in Paris in the early 1960s marked a pivotal moment in his intellectual development. This period, which can be termed the “Fanonian interlude,” profoundly influenced Shariati’s thinking on colonialism, cultural authenticity, and revolutionary change. Fanon’s critique of colonialism and his emphasis on the psychological dimensions of oppression resonated deeply with Shariati, who saw parallels between Fanon’s analysis of the Algerian struggle and Iran’s own experiences with Western domination.

The Fanonian influence is evident in several key aspects of Shariati’s thought. First, like Fanon, Shariati emphasized the importance of cultural decolonization as a prerequisite for genuine political and economic independence. He argued that Iranians needed to free themselves from the mental shackles of Western cultural hegemony and rediscover their authentic Islamic-Iranian identity. This notion of “Return to the Self” (Bazgasht be Khish) became a central theme in Shariati’s writings, echoing Fanon’s call for a new humanism rooted in the experiences of the colonized.

Second, Shariati adopted Fanon’s critique of the national bourgeoisie and their role in perpetuating neo-colonial structures. He argued that Iran’s modernizing elite, in their uncritical embrace of Western models of development, had become alienated from the masses and were incapable of leading genuine social transformation. Instead, Shariati, like Fanon, placed his hope in the revolutionary potential of the marginalized and oppressed.

Third, Shariati’s conception of religion as a revolutionary force owes much to Fanon’s insights into the role of culture in anti-colonial struggles. While Fanon focused on national culture as a source of resistance, Shariati saw in Islam, particularly its narratives of martyrdom and social justice, a powerful resource for mobilizing the Iranian masses against both domestic tyranny and Western imperialism.

The Fanonian interlude in Shariati’s intellectual development had far-reaching consequences for Iranian political thought. By infusing a particular Islamic discourse with the language of Third World liberation struggles, Shariati created a powerful ideological framework that appealed to both religious and secular opponents of the Shah’s regime. His ideas played a crucial role in mobilizing Iranian youth and intellectuals in the lead-up to the 1979 revolution.

Yet, the legacy of Shariati’s Fanonian-inspired thought remains contested. Critics argue that his romanticization of “authentic” Islamic identity and his emphasis on cultural purity laid the groundwork for the exclusionary policies of the post-revolutionary Islamic Republic. Supporters, on the other hand, maintain that Shariati’s vision of a progressive, socially just Islam has yet to be fully realized and remains relevant to contemporary struggles for democracy and social justice in Iran and the broader Muslim world.

Dr Ayesha Omar is a senior lecturer in political studies at the University of the Witwatersrand and is currently a British Academy International Fellow at SOAS, University of London. She is working on a new book project on Black Intellectual History in South Africa.