By Faseeg Manie

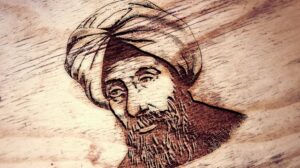

It is with deep humility, gratitude, and a profound sense of responsibility that I introduce my recently completed book, Imam Gassan Solomon – Moral Revolutionary of the Mimbar.

This is not simply a biography. It is a tribute. A remembrance. A resistance against forgetting. A small act of fidelity to the truth and legacy of a man whose life continues to echo in our hearts, our mosques, and our movements.

The decision to write this book grew from an urgent feeling: that too many of our stories, especially those of Black South Africans who stood at the forefront of justice, are being erased or sidelined. In our national consciousness, the contributions of giants like Imam Gassan Solomon are not always given the honour they deserve. Their courage is often flattened, their spiritual leadership reduced, their resistance too easily forgotten.

This book is my humble offering to correct that.

Imam Gassan Solomon was a towering figure, not only in the history of South African Islam but in the broader struggle for justice, freedom, and dignity, from the Claremont Main Road Mosque pulpit, where he denounced apartheid with fearless conviction. As a political leader, he became a principled member of Parliament representing the African National Congress.

As a mentor and senior member of the Muslim Youth Movement of South Africa, he inspired generations of youth to connect their faith to action. And as a human being, he radiated love, joy, and humility.

But before he was any of these things, he was a young boy raised by devout and principled parents. His father taught him the value of groundedness, of knowing the land, working with one’s hands, and practising the ethics of ḥalal living. His mother ignited his love of books and independent thought. Both of them planted in him the seeds of ʿadl (justice) and ihsan (compassionate excellence), qualities that came to define his leadership.

His upbringing in the Constantia Village of Cape Town, where his grandfather’s farm welcomed people of all races and religions, offered a lived lesson in inclusion. Long before the phrase “interfaith solidarity” became common, Imam Gassan was embodying it. These experiences instilled in him an Islam that was not afraid of the world, but engaged with it, transformed it, and loved it.

Imam Gassan loved learning. He completed his studies under immense pressure, even while living in safe houses during apartheid. He read widely, engaging deeply with the writings of al-Ghazali, Sayyid Quṭb, Shariati, as well as Sartre and Marx.

He was one of the first South African Imams to draw meaningful connections between Islamic spirituality and historical materialism. But his intellect never made him inaccessible. He was a man of the people who could speak to a worker, a child, or a parliamentarian with equal warmth. And he lived fully. He enjoyed jazz music, spicy food, soccer, fishing, and kite-making with his grandchildren. He showed us that joy and resistance are not contradictory. That a life of faith is also a life of beauty.

His political awakening was not sudden, but the result of painful encounters with injustice: the 1959 Extension of University Education Act, the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, his family’s 1966 forced removal from Constantia, and the 1969 death of his mentor, Imam Abdullah Haron. These moments etched upon his soul the urgent truth that silence in the face of injustice is not an option.

Throughout the 1980s, Imam Gassan became a major target of the apartheid regime. He evaded capture multiple times, disguised in a janazah bier, hiding in an ambulance, outwitting police even at this very mosque. Eventually, he went into exile. But his voice, his moral clarity, never left. If I had to describe him in one phrase, it would be this: a moral revolutionary.

Not just a scholar or political figure. He was a bridge between the sacred and the secular, the mimbar and the movement, the Qur’ān and the streets. He did not see Islam as a private refuge but as a public responsibility. He believed that prayer, fasting, and spiritual devotion must be linked to social justice, political integrity, and the defence of the voiceless. He insisted that Islam must never be reduced to identity or ritual. It must be lived as a force of liberation.

His work with the United Democratic Front, the Call of Islam, and his fearless khutbahs were all part of a single, coherent message: faith without justice is hypocrisy. He stood in solidarity with Christians, Jews, and secular activists, not despite his Islam, but because of it.

This book also explores his mentoring of youth. He did not raise followers; he nurtured thinkers. He wanted young Muslims to ask: What does Allah require of us in the face of oppression? He helped a generation to connect the Qur’ān to protest, and the Sunnah to sacrifice. In our current moment of global disorder, from apartheid in Palestine to spiritual decay in our own communities, Imam Gassan’s legacy could not be more relevant. He reminds us that Islam is not about isolation. It is about courageous engagement. He calls us to ask: What does it mean to be Muslim when bombs fall, when hunger spreads, when truth is silenced?

I wrote this book because I believe his legacy is not over. His work is not finished. His memory is not a relic of the past it is a summons to the present. This masjid, this city, this country still needs his voice My hope is that readers, young and old, will come to see in Imam Gassan a mirror and a map. A mirror that reflects what faith should look like when rooted in truth. And a map for how we must live, lead, and love in a broken world. I offer this book not as a final word, but as an invitation. Let us not just admire Imam Gassan’s life. Let us live it. May we be the echoes of his freedom.

*About the Author: Faseeg Manie is a retired educational leader with over 40 years of experience transforming underperforming schools in economically disadvantaged areas of the Western Cape. His career began in the 1980s at Westridge High School in Mitchells Plain, where he implemented creative and innovative methods for teaching English, effectively addressing the challenges of under-resourced environments.