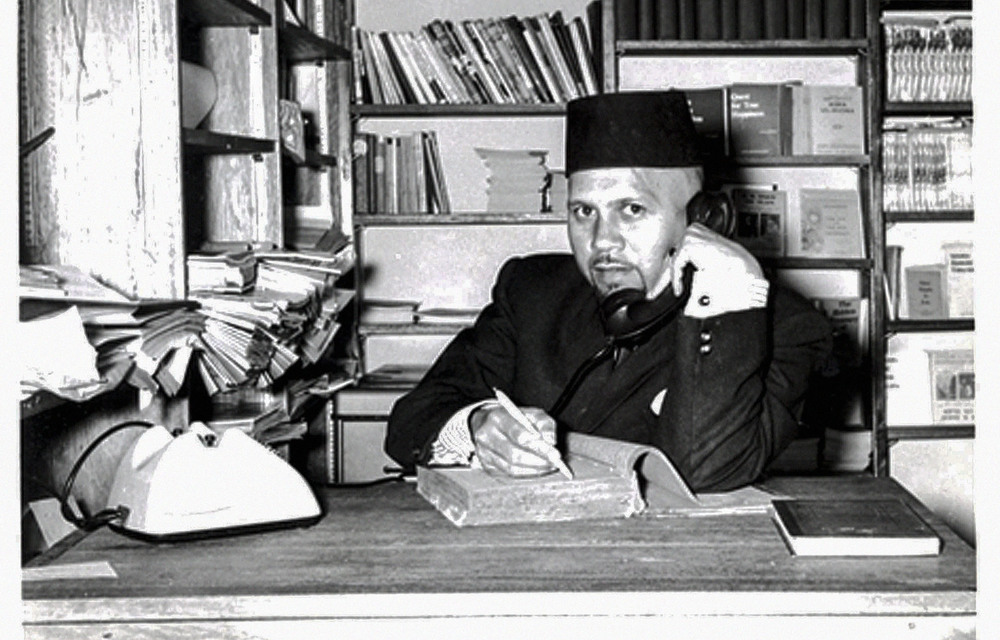

[Photo credit: Mail & Guardian]

By Najwa Norodien-Fataar and Aslam Fataar

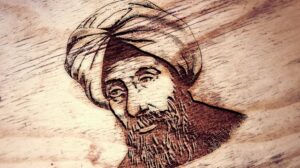

The inquest into the brutal killing of Imam Abdullah Haron in 1969 raises the question about the meaning and purpose of this momentous event. This question arose as we watched the inquest on YouTube and in court. We witnessed pathologist Dr Segaran Ramalu Naidoo explain painstakingly the injury and trauma that the Imam was subjected to during the four months of his incarceration that led to his death and martyrdom.

Dr Naidoo built a persuasive, grim and gruesome case of the systematic torture and violence meted out on the Imam’s body. He described the clusters of wounds on the body, their external markings, and the internal wounds and trauma caused by the torture. We reminded ourselves that the Imam refused to budge, never revealing any information on his underground activities or associates.

We had to remind ourselves of the depravity and degradation of the torturers who inflicted this violence on the Imam. As it did this past Thursday, the medical explanation was presented in precise, cold, and clinical detail. Such a presentation is a requirement because the court must be persuaded by the hard evidence of trauma meted out on the Imam’s body.

Yet, the people who inflicted the torture tended to be missing from the description. It was up to us in the audience to remind ourselves that there were human beings who did the torturing, and they represented the apartheid state. They were the enforcers in a racially depraved police state and its violent infrastructure. They came from families who nurtured them to believe they were acting in service of the volk and the nation. This nurturance is borne of the banality of evil that Hannah Arend described when she puzzled over the Nazi enforcer, Adolf Eichmann, who was apparently a ‘normal’ person despite his barbarism.

Eichmann was apparently a bland bureaucrat’. He acted to diligently advance his career in the Nazi bureaucracy. He performed evil deeds in a blasé manner. He was seemingly thoughtless, disengaged from the reality of his evil acts. This banality of evil may have characterised Imam Haron’s torturers’ intentions and actions.

They could not comprehend or feel their wrongdoing. After all, they worked in service of the volk. This is a bitter pill because, 53 years after the Imam’s killing, his killing is rendered a ‘perpetratorless’ crime. None of the perpetrators will be tried for the killing, and no one will be held accountable.

Sitting in court on Thursday, it dawned on us that the inquest may not be the truth-telling platform for the family and community’s restitution and healing. It may come closer to the truth though. The brutal fact is that these apartheid apparatchiks have hitherto remained utterly faceless. Or at least none of them have been called to account, from the venal politicians right at the top to the tribal policymakers, bureaucrats, and police enforcers. They were the humanity-redux enforcers of tortuous deprivation against the oppressed masses and activists who opposed the apartheid regime.

In response to the inquest, friends, Yumna and Najwa’s (co-author of this article) comments on a Facebook thread show the consequence of the ‘perpetratorless’ or faceless depravity that accompanied the Imam’s killing and this inquest decades later. Yumna explained that,

“My dad was very close to the dear Imam. This morning I was having a conversation about the day he died. He explained to me how Imam’s wife responded to his death, how his brother did not know, and my dad told him because he got onto the same bus my dad was taking to go to Imam’s house. How did Imam’s brother respond to news of his brother’s death? He also told me of how someone told him that he witnessed Imam being kicked in sujud (prostration) by the police. This triggered me because, just before we started chatting, I listened to part of the pathologist’s testimony and identified a possible wound that corresponds to what my dad said. I then played the video clip to him; he was lying in bed, convalescing because of an aortic aneurysm. He watched for a minute, and when the description became more graphic, he asked me to switch it off. I could see the pain in his eyes and on his face. He said, leave it. Let him rest. He has not been following the inquest because of his health, but I also think the energy he requires is pure bravery because it is like reliving a reality that was so painful and extremely vividly etched into his memory. He was the last person to climb out of the grave when they buried Imam.”

Najwa, whose grandmother, Mariam (AKA Koning), was part of the family of Imam Haron, explained on the same Facebook thread that,

“My father often spoke about Imam Haron and narrated the story of his janaza to our family. He told the story about his unjust death at the hands of the apartheid police. I was born on 25 September 1969, and Iman Haron died on 27 September. Cape Town experienced a tremor, and the Muslim community believed this was a sign from God that an injustice had occurred. These are some of the oral stories told by a generation that lived during the most brutal days of apartheid. Their lives were viciously controlled, regulated, and violated by the authoritarian laws of apartheid. The decision by the apartheid government to torture and brutalise an Imam shows the extent to which the apartheid police oppressed the black, coloured, and Indian people of South Africa. As I read your account of your father and how he struggles to talk about the pain that he is going through, I can only imagine the trauma and grief that my father and others in the Claremont community experienced during those days. How does the family deal with the grief? How do communities deal with grief?

Aslam (co-author of the article) offered a bland response:

Hi Yumna and Najwa; both of you raise critical and interesting perspectives. It strikes me that our apartheid-ravaged families and communities may have immense unresolved transgenerational trauma. The inquest is opening raw wounds that may have been submerged yet haven’t been processed properly. My embrace to Boeta Doud [Dawood Hattas, is Yumna’s father]. Perhaps the inquest gives the community and families another chance to process the trauma of the Imam’s killing and the apartheid-inflicted wounds that still sit with us.

Yumna and Najwa’s comments show the unprocessed trauma that sits with families in Claremont and others close to Imam Haron. This trauma is now being passed on to future generations. These families have hitherto not been able to mourn the Imam’s death properly.

Without a formal investigation and acknowledgement by the state, the community may be in a condition of ‘ungrievability’. In other words, the lack of an explanation and disclosure of Imam’s torture and killing by the apartheid regime may have prevented affected families from properly processing Imam’s death. They may struggle to enter a period of mourning and grief, pick up the emotional pieces, and figure out ways of moving forward free from the psychological shackles imposed by the lack of full disclosure and acknowledgement.

Najwa and Yumna’s fathers’ stories are of unresolved pain, heartache, and trauma. Boeta Doud can barely listen to the inquest testimony, having had the honour of interring the Imam’s body into the ground during the burial. The inquest seemed to have broken him, transporting him back 53 years to Imam’s detention and funeral. The association with the apartheid regime’s murderous ways would have been palpable. And Boeta Doud would have lamented the devastation caused by apartheid on families in Claremont. They were forcibly removed to the desolate Cape Flats, where they had to pick up the pieces of their harsh family lives.

Their daughters, Najwa and Yumna, have inherited aspects of the trauma of the Imam’s death and the brutality of apartheid. They are possibly passing the trauma on to their own children. Interrupting the narrative of ‘ungrievability’ has hitherto not yet emerged. Imam Haron’s killing may not yet have been adequately mourned.

The inquest presents an opportunity to usher in the possibility of proper grieving and mourning. The inquest is pursued on the promise that getting to the truth, or a fuller, more plausible version of his detention, torture, and death, would provide a basis for properly grieving Imam Haron’s death. Fuller knowledge of the Imam’s death promises to give families and communities a foundation for entering psycho-therapeutic processes of rupture, remorse, recovery, and healing.

The inquest promises to serve as a galvanising platform for interrupting the transgenerational trauma suffered by families and communities. This means that we must find ways of moving the inquest and its outcomes from the court into our community’s institutions, such as churches, mosques, social welfare operations, media, schools, universities and colleges. This is where we would be able to do the necessary counselling, educational and dialogical work within communities to interrupt and build skills to address community and individual trauma. The inquest into the killing and death of Imam Haron offers us such an opportunity.

Dr Najwa Norodien-Fataar is an academic at the Cape Peninsular University of Technology and Prof Aslam Fataar is attached to Stellenbosch University.